|

| November 17, 2020 | Volume 16 Issue 44 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

55 Years Ago: NASA Gemini 5 sets a new record

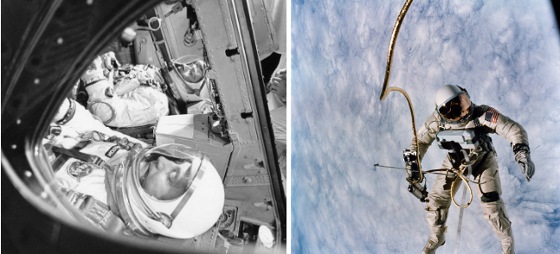

Workers in the White Room at Launch Pad 19 help Command Pilot L. Gordon Cooper (left) and Pilot Charles "Pete" Conrad strap in to Gemini 5

Project Gemini: Two Gemini missions were flown in 1964 and 1965 without crews with the aim of testing systems and the heat shield. Ten crewed flights followed in 1965 and 1966. All were launched by Titan II launch vehicles.

By John Uri, NASA Johnson Space Center

The primary goals of Project Gemini included proving the techniques required for the Apollo Program to fulfill President John F. Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s. The series of two-man Gemini flights followed the successful completion of Project Mercury that placed America's first astronauts into orbit.

Paramount among the techniques demonstrated during Project Gemini was rendezvous and docking necessary to implement the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous method NASA chose for the Moon landing mission. Additional goals of Gemini included proving that astronauts could work outside their spacecraft during spacewalks, or Extravehicular Activities (EVA), and ensuring that spacecraft and astronauts could function for at least eight days, considered the minimum time for a roundtrip mission to the Moon.

Left: Gemini 3 astronauts Grissom (foreground) and Young in their capsule prior to launch. Right: Gemini 4 astronaut White during the first American spacewalk.

The first two Gemini missions flew without a crew to validate the spacecraft's design and reliability, especially of its heat shield. Astronauts Virgil I. Grissom, the first person to enter space twice, and John W. Young flew the first Gemini mission to carry a crew, Gemini 3. During their three-orbit flight, they validated the spacecraft's life-support systems and performed the first orbital maneuvers, critical for future rendezvous missions.

Astronaut Edward H. White completed the first American EVA (spacewalk) on June 3, 1965, during Gemini 4, and along with James A. McDivitt he completed a four-day flight that was the longest American mission up to that time. The primary goal of Gemini 5 was to fly in space for eight days, proving that astronauts and their spacecraft could function for the expected duration of a lunar landing mission.

The extended duration meant that the spacecraft could no longer rely on just batteries for power but instead used fuel cells that produced electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen, creating water as a byproduct. At eight days, Gemini 5 would spend more time in space than all previous American missions combined. A rendezvous simulation test was also part of Gemini 5's mission plan, as were a series of scientific experiments.

Left: Engineers at McDonnell prepare the Gemini 5 spacecraft for shipment to the launch site. Right: Gemini 5 prime and backup crews during the preflight press conference (left to right) See, Conrad, Cooper, and Armstrong.

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation built the Gemini spacecraft at its St. Louis, Missouri, plant while the Martin-Marietta Corporation assembled the Titan-II rocket in Baltimore, Maryland. For the Gemini 5 mission, on Feb. 8, 1965, NASA named Mercury veteran L. Gordon Cooper as the Command Pilot and space rookie Charles "Pete" Conrad as the Pilot, as well as Neil A. Armstrong as back-up Command Pilot and Elliot M. See as back-up Pilot, both rookies.

Cooper decided that he and Conrad needed a patch for their mission, so he designed one that included a Conestoga covered wagon to symbolize the long journey. He also added the words "8 Days or Bust" to the patch. After much discussion, NASA Administrator James E. Webb reluctantly approved the patch on the condition that the motto be covered out of concern that if for whatever reason the flight didn't last the full eight days the media would label it a bust.

Left: Gemini 5 crew of Conrad (left) and Cooper at Launch Pad 19. Right: Gemini 5 patch with the motto (left) and with the motto covered up.

On Aug. 21, 1965, chief astronaut Donald K. "Deke" Slayton woke Cooper and Conrad to help prepare them for launch. They ate the traditional steak and eggs breakfast and left crew quarters at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) to don their spacesuits in the trailer at Pad 16 of the Cape Kennedy Air Force Station (CKAFS). From there, they took the transfer van to Pad 19 where their Titan-II rocket awaited. They took the elevator to the launch tower's 11th level, where McDonnell pad chief Guenther Wendt and his team secured Cooper and Conrad into their seats and closed and sealed the hatches of the Gemini spacecraft.

Left: Conrad (left) and Cooper (center) at the traditional pre-launch breakfast with Slayton (right). Right: Workers in the White Room at Launch Pad 19 help Cooper (left) and Conrad strap in to Gemini 5.

When the countdown clock reached zero, the Titan-II's first-stage engines ignited and the Gemini 5 mission was underway. Five-and-a-half minutes after launch, the second stage engine cut off and the spacecraft separated to begin its orbital journey, Cooper becoming the first human to orbit the Earth a second time.

While the countdown was monitored from the Gemini Launch Control Center at Launch Complex 14 at CKAFS, once in orbit flight controllers in the Mission Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, took over. Gemini 5 was only the second flight controlled from the new center.

Liftoff of Gemini 5 from Pad 19.

About two hours after reaching orbit, the astronauts commanded the ejection of the Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP) from the aft Adaptor Section, turned their spacecraft around, and immediately their radar locked onto the REP. The pod appeared to move straight out from the spacecraft as the astronauts continued to track it with their radar, with the intention of attempting a rendezvous with the target.

Gemini Launch Control Center, with Chief Astronaut Slayton (standing) and Capcom astronaut Russell L. "Rusty" Schweickart (seated in black shirt).

During this exercise, Conrad noticed that the pressure in the oxygen tank that fed the fuel cells had dropped. Mission Control, led by Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft, instructed him to switch on a heater to raise the pressure, but the pressure remained low. Because the fuel cells were critical to ensure that they could remain in orbit for eight days, the crew turned off non-essential equipment in the spacecraft to conserve power and terminated the rendezvous exercise.

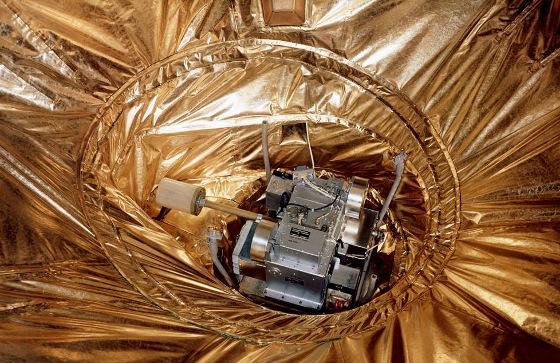

Preflight photograph of the Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP) stowed in the Gemini spacecraft's aft adaptor section.

The next two teams of controllers, led by Flight Directors Eugene F. Kranz and John D. Hodge, resolved the problem as the oxygen tank pressure stabilized and they allowed the crew to turn equipment back on. The crew began some experiments before attempting to get some sleep, first by alternating sleeping then realizing that wouldn't work, so they tried sleeping at the same time. They continued their experiments on the second day, including taking photographs of the Earth.

Panoramic view of the Mission Control room at MSC during the Gemini 5 mission.

During their third day in space, Cooper and Conrad conducted four engine burns to simulate the rendezvous profile planned for the Gemini 6 mission, all of which they completed successfully.

Views of the Earth taken by the Gemini 5 crew include Cape Canaveral, FL (left); Baja California, Mexico (center); and the Salton Sea, southern California (right).

Over the next few days, the Gemini 5 astronauts continued their experiments and Earth photography, with the spacecraft partially powered down. They observed some pre-arranged targets on Earth, including the contrail of a chase plane and the associated missile launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base (AFB) in California. They observed their prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier USS Lake Champlain (CVS-39), in the Atlantic Ocean.

On the fifth day, the first of several attitude control thrusters failed, giving Mission Control some concern as to whether the flight could continue. By allowing the spacecraft to drift, with only occasional thruster firings to stop excessive tumbling, the astronauts were able to live with the failed thrusters. They also completed a suite of medical experiments to monitor the effects of their long mission.

At 119 hours and six minutes into the flight, Gemini 5 became the longest crewed space mission, surpassing the mark set by Soviet cosmonaut Valeri I. Bykovski aboard Vostok 5 just two years earlier.

Left: Shortly after splashdown, swimmers assist Cooper (left) and Conrad to transfer from their spacecraft into a life raft. Right: Conrad (left) and Cooper compare their 8-day beards on the deck of the USS Lake Champlain.

On the morning of Aug. 29, in darkness over Hawaii, Cooper and Conrad fired Gemini 5's retrorockets to reduce their velocity enough to fall out of orbit. After jettisoning the spacecraft's Adaptor Section, the capsule began to encounter the upper layers of the Earth's atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet.

The buildup of ionized gases caused a temporary loss of communication between the spacecraft and Mission Control. At 39,000 feet, Cooper commanded the deployment of the drogue parachute to stabilize and begin slowing the spacecraft's descent. The main parachute was deployed at 10,600 feet.

After a flight of 190 hours and 55 minutes, Gemini 5 splashed down about 98 miles short of the planned target, the error due to an incorrect parameter programmed into the guidance computer before the mission. Despite the undershoot, a helicopter recovered Cooper and Conrad and delivered them to the deck of the Lake Champlain within 90 minutes. Although both had lost weight, they were in good physical condition after their record-breaking eight days in space.

Cooper (left) and Conrad welcomed home at Ellington AFB.

The day after splashdown, Cooper and Conrad were flown to KSC for debriefings and a continuation of the medical examinations begun on the carrier. Chief physician for the astronauts Dr. Charles A. Berry said the astronauts were in good health after their record-setting mission, and he saw no indications that a planned 14-day mission for Gemini 7 would cause any problems.

The astronauts returned to Ellington AFB in Houston on Sept. 2, greeted by 500 well-wishers and reunited with their families. On Sept. 9, Cooper and Conrad held a press conference, along with MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth and Robert C. Seamans, NASA Associate Administrator, to provide a summary of their mission.

In a ceremony at the White House on Sept. 14, President Lyndon B. Johnson conferred NASA Exceptional Service Medals on Cooper, Conrad, and Dr. Berry. They and their families, accompanied by Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, went to the Academy of Sciences where they gave speeches, then traveled via a motorcade to the Capitol where Cooper and Conrad addressed the House of Representatives and were introduced to the Senate.

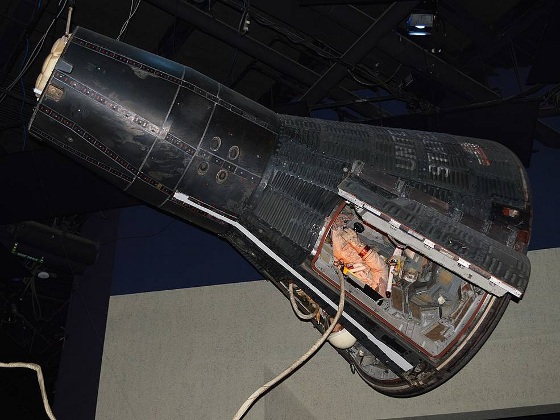

The Gemini 5 spacecraft on display at Space Center Houston.

From Washington, DC, starting on Sept. 15 Cooper and Conrad and their families embarked on a 13-day six-nation goodwill tour to Greece, Turkey, Ethiopia, the Malagasy Republic, Kenya, and Nigeria, with a final rest stop in the Canary Islands, assigned to them by President Johnson. At a State Department luncheon prior to their departure, attended by ambassadors from the six countries they would visit, Cooper said that from Gemini 5, "You don't see any of the combat, you don't see any of the fighting and bickering, the world looks like a very peaceful place."

During their stop in Athens, they attended the International Astronautical Congress and met with the crew of Voskhod 2, Soviet cosmonauts Pavel I. Belyayev and Aleksei A. Leonov, who completed the first walk in space six months earlier. During their goodwill tour, NASA assigned Conrad as the back-up Command Pilot for Gemini 8. Cooper and Conrad returned to Houston on Sept. 28.

The Gemini 5 capsule is currently on display at Space Center Houston.

Read more NASA history stories at nasa.gov/topics/history/index.html.

Published November 2020

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy